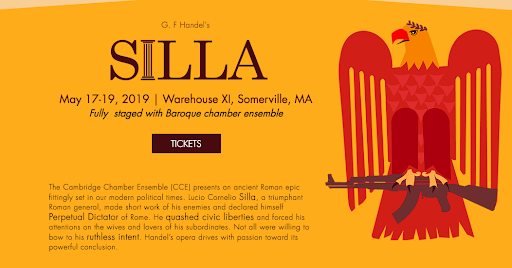

Presented by The Cambridge Chamber Ensemble

Music by G.F. Handel

Libretto by Giacomo Rossi

Music Directed by Juliet Cunningham

Stage Directed by Ingrid Oslund

Produced/Executive Direction/Translation by Martha Birnbaum

Rossana Chung, violin

Rob Bethel, violincello

Lisa Putukian, oboe

Juliet Cunningham, harpsichord

Warehouse IX

Somerville, MA

The Cambridge Chamber Ensemble on Facebook

Review by Gillian Daniels

(Somerville, MA) Roselin Osser as Silla has the wild eyes, swagger, and exquisite cheekbones of a villain as he dominates the stage. In this alternate version of 2019, the Roman Republic is alive and well and Silla, after a successful military campaign, announces that he plans to rule as Perpetual Dictator of Rome. The reporters are horrified. Silla’s wife, Metella (the hilarious Theresa Egan) grits her teeth and stands by her man. As Silla begins to openly lust after other women and jail his political enemies, however, Melania–I mean, Metella, yes, begins to wonder just how much her loyalty to a tyrant husband is worth.

As you might be able to tell from the synopsis, and if you’re a cognizant being who follows the vaguest stories about the current administration, Silla hits some notes that are fairly close to home. The opera maps awkwardly onto our own world, however, as the titular tyrant, in operatic convention, refuses to violate the women in his orbit without their consent. I guess you can say an entitled ruler who oscillates between inappropriate lust and violence is not unique to this decade, much less this continent, though I admire the mash-up here.

The closest parallel I found between current events and the show is the initial rift between young couple Claudio (the assured Lucas Coura) and Celia (played with endearing, wide-eyed innocence by Gyuyeon Shim). The former works to uncover the cruelties Silla visits on others in the name of the Republic, specifically an off-screen refugee crisis. The latter is blinded by Silla’s egotism, becoming a passionate devotee. Their fight has a rhythm familiar to those who have watched loved ones merrily throw on racist MAGA hats and rage on Facebook about how “no one respects the president, anymore!”

Contemporary allusions and fascinating idea aside, the production ultimately didn’t gel for me. Setting a show about the Roman empire in the 21st century makes the story feel unadorned, even sedate. This production just doesn’t feel particularly out there for a show about a ridiculous ruler’s cruelties and excesses.

Its biggest strength is the interpretation of the music and the libretto’s translation. I found myself moved by Juliet Cunningham’s accompanying harpsichord not to mention the romantic duets between Flavia (Stephanie Mann, a formidable presence) and her lieutenant husband, Lepido (Ann Fogler).

The stage is at its most lively during visits from the god of war, Mars (Fran Daniel Laucerica). In a dream had by Silla, Mars and his chorus joyfully shout for blood and violence. It’s a vibrant moment. Laucerica brings a buoyancy and humor to the stage that makes the rest of the show seem grim. He offers the same enthusiasm in a later scene when Metella sends her prayers to the god.

Among the show’s other virtues, I admired how its casting. Feminine-presenting thespians are given the roles of rulers, lieutenants, and bouncers. Put-upon-wife Metella’s comic timing is a great deal of fun, whether she’s rolling her eyes as Silla makes a pass at Flavia or knocking back wine as she bemoans the fact that, for all her patience, Silla disregards her repeatedly. Egan seems to be having a great deal of fun.

Silla, tonally, wanders between that same wry sense of humor and stern, hard-to-stomach violence but doesn’t wholly commit to either. If the production was trying for a lighter feel, it should have made more boisterous, even campy choices. If the latter, the stage needed more blood. Murder is alluded to but does not make its way to bloody any of the immediate hands of this cast. The horrors of our current moment are reflected awkwardly. Claudio at one point shouts, “Times up!” when Flavia loudly refuses Silla’s advances. The moment is clunky, highlighting what was mined with far more thought and organic resonance in Boston Opera Collaborative’s Don Giovanni last month. I admire the experiment attempted here, though, and found the music lovely, but I wish it had stuck the landing.