Alejandra Escalante, Kate Hamill, Nike Imoru, and Wayne T. Carr in The Odyssey.

Photo: Nile Scott Studios and Maggie Hall

Presented by American Repertory Theater

Written and adapted by Kate Hamill

Based on the epic poem by Homer

Directed by Shana Cooper

Dramaturgy HERE

Digital Playbill HERE

Feb 11 – Mar 16, 2025

Loeb Drama Center

64 Brattle Street

Cambridge MA 02138

This production contains sex, violence (including the death of children and animals), and references to sexual assault, as well as fog, haze, strobe, and flashing lights.

Recommended for ages 14+.

“As a feminist playwright, I believe deeply in creating female-driven narratives and reclaiming the classics for people of all backgrounds and genders. My Odyssey is narrated by the three female Fates, who literally haunt Odysseus as the spirits of the women of Troy; women drive the story. Not only warriors bear the cost of war, and it’s easy to lose the stories of how often women and children are the victims of brutal conflict around the world.”

-Adaptor Kate Hamill in “A Note from Kate Hamill” on the A.R.T. website

CAMBRIDGE, MA — Kate Hamill’s The Odyssey running at the American Repertory Theater reimagines its title character Odysseus if he were just a guy. In Homer’s epic poem and the adapted play, Odysseus makes terrible choices which he conveniently blames on the gods and mortal women if he doesn’t like the consequences. The Odyssey reminds us that myths provide moral guidance that modern entertainment does not; when we remove the fantastical from our myths, we’re left with stories about everyday people ignoring red flags and turning from society’s fundamental principles of dignity, loyalty and honesty.

Public schools have been teaching Homer’s The Odyssey for decades. It’s been turned into movies and T.V. serials. It’s inspired numerous fanfictions. Margaret Atwood’s 2005 The Penelopiad was made into a play for the Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon, England in 2007. It’s a fast read that pays homage to Atwood’s novel and Homer’s antagonized heroine. There’s even a 1987 episode of the original DuckTales entitled “Home Sweet Homer” loosely based on Homer’s poem. There are oodles of opportunities to know The Odyssey without reading the original… Which can be tricky to read and absorb depending on the dry clunkiness of the translation. Fortunately, Hamill’s play is anything but.

Like Homer’s work, Hamill’s The Odyssey begins ten years after the Trojan War depicted by Homer’s The Iliad. Odysseus (Wayne T Carr) is suffering from wartime PTSD and self-medicating chronic depression with unprotected sex and alcoholism on a remote island with his soldiers (Benjamin Bonenfant, Carlo Alban, Keshav Moodliar, Jason O’Connell, Chris Thorn) when he is inspired “by the gods” to finally return home to his loving wife. He is accompanied by three women – Maiden (Alejandra Escalante), Mother (playwright Kate Hamill), and Crone (a resplendent Nike Imoru) – who narrate his adventures.

Meanwhile, back in Ithaca, Penelope (Andrus Nichols), Odysseus’ devoted wife, has faithfully hosted per Greek custom a legion of male suitors itching to take Odysseus’ place as King. She believes Odysseus is still alive; the suitors, who prove why women choose the bear, do not. They won’t leave until Penelope marries one of them. Desperate to buy Odysseus more time to get his wandering butt home, Penelope tells the suitors – in a cunning plan of weaponized incompetence – she may only wed Odysseus’ successor after weaving his burial shroud. This #ladyboss fools her carousing, drunken suitors for ten more years*.

As the years pass, Odysseus winds his way across the seven seas to meet a series of violently unhinged characters: Polyphemus the Cyclops, Circe (playwright Hamill kicking pork and taking names) who brings Odysseus to the underworld to speak with his mother Anticlea (Imoru), and Nausicaa (Escalante) on the isle of Helios. Antiquity has taught us Odysseus’ ultimately finds his way home. Whether he is welcomed and if he welcomes it in return is up to him.

Hamill is unhinged as the truth-telling goddess/witch Circe. Performance is a no holds barred attack on traditional acting of the theatre. Her character is feral and Hamill leads with her instincts. Circe’s the woman naughty little girls with no boundaries want to be when they grow up: humping on tables, and seducing adult men into their own murder. Most of us end up like Penelope – who is lovely if that’s what you want. Being Circe takes discipline and hard work to dismantle one’s inner patriarchy. We love to see it.

The Odyssey Production Photo

Wayne T. Carr, Kate Hamill, Alejandra Escalante, and Nike Imoru in The Odyssey.

Photo: Nile Scott Studios and Maggie Hall.

Abigail Baird’s shadow puppetry in collaboration with the projection work by Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew is deeply compelling. In the Polyphemus scenes, Jason O’Connell as the Cyclops hulks to stage left before a blinding stage light to cast a shadow onto a scrim. On it, a giant evil eye stares down at Odysseus and his cowering men. A squint later and one of the soldiers disappears down Polyphemus’ shadowy gullet. The terrified reactions of the players onstage are reflected in the audience’s faces.

The original music compositions by Paul James Prendergast catapult the play through Odysseus’ bad choices. When they land on Circe’s isle Aeaea, Odysseus and his men hear musical moaning through the trees. It’s a promise of physical delights to come. Penelope’s suitors dress in fur coats and sunglasses to catchy Euro-trash techno beats; it tells us who these men are and what to expect from them. As they sail to the sirens, Odysseus’ crew is lured by Prendergast’s song which incorporates the sweet voices of loving, forgiving mothers calling out to their sons. The sirens’ reveal is more horrifying for its juxtaposition again the sirens’ deathly costumes by Sibyl Wickersheimer.

Hamill’s Odyssey is decisively intersectional feminism. Maybe not for the reasons you’d expect. Yes, sure. Penelope has a voice and a journey but, in most adaptations, she doesn’t talk to a woman about something other than a man. Meaning, she doesn’t pass the Bechdel Test. The Bechdel Test is the barest of minimums for feminist media.

Rather, The Odyssey is a feminist work because our hero Odysseus is viewed as a fully human, imperfect being with wins and huge losses who shares his feelings with *gasp* Other. Men. He’s fallible, unlikeable and still our brave hero. With Polyphemus, Odysseus taunts the Cyclops and gets an ego punch to the nads when his men die. He mourns and celebrates when the survivors are free. When Odysseus is with Circe, he throws a tantrum and accuses her of lying when she has only told him the truth. Circe is a three-dimensional character with motivations, a ripe past, and an existence outside of what she provides for Odysseus. On Helios, Odysseus looks to Nausicaa for a new life to escape his past. Nausicaa, an Apollonian Priestess, loves Odysseus and then leaves him once she learns who he truly is. She exists outside of Odysseus’ struggle for absolution. She, like all women, is more than what our hero can take from her.

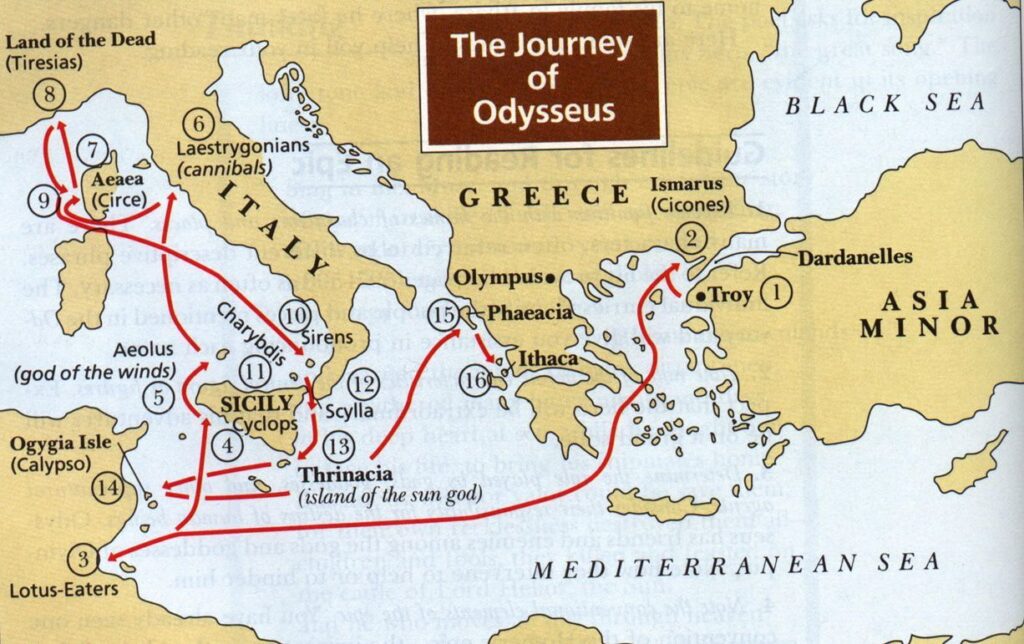

Speaking of which, The Odyssey is about a psychological journey as well as a physical journey. At each stop on his long way home, Odysseus looks outside himself for absolution for the crimes he committed during the Trojan War. He tries to forget himself in drink, sex, and murder but always returns to his tortured self. Odysseus, just like any human man, must find forgiveness in himself before he can claim it from others. When Odysseus is denied the healing he feels entitled to by the women whose lives he upturns, he lashes out like a child on meth again and again.

The Odyssey is a grand epic tale told over three hours. It’s decisively feminist and unhinged in the best ways. If you’ve enjoyed Kate Hamill’s other adaptations, you’ll enjoy this one, too.

*Odysseus, my guy, if you wanted to go home, you would. Please seek therapy.

Thanks, Reddit, for the map.