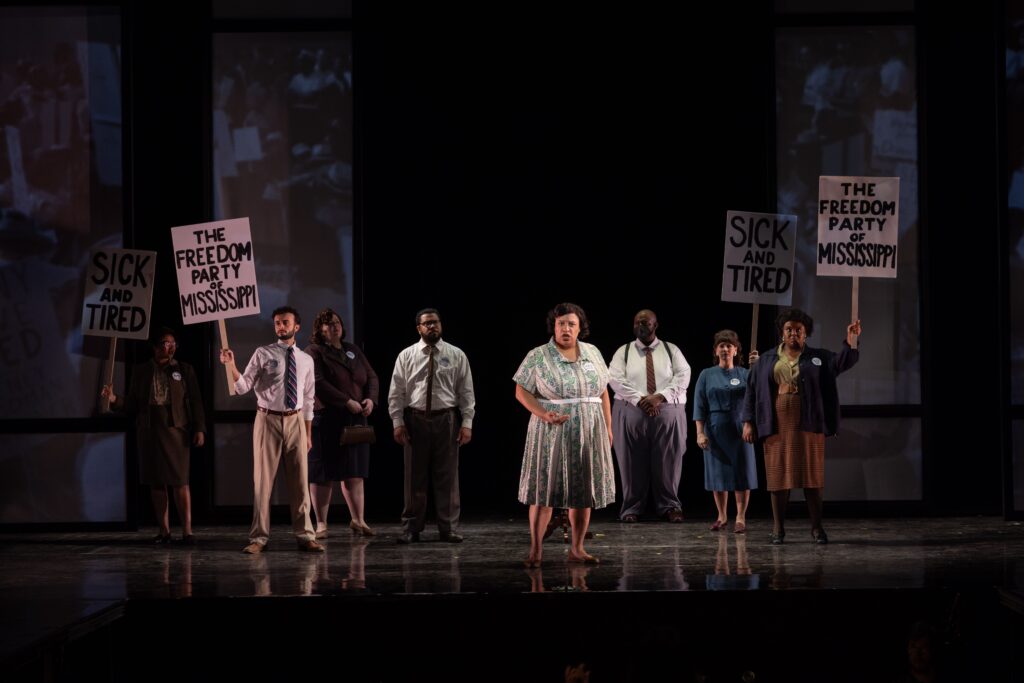

The ensemble. Photo by by Kathy Wittman.

Presented by White Snake Projects

Composition by Mary D. Watkins

Libretto by Mary D. Watkins and Cerise Lim Jacobs

Stage direction by Pascale Florestal

Music direction by Tianhui Ng

Projection design by John Oluwole ADEkoje

Scenic design by Baron Pugh

Program art by Dr. Nettrice R. Gaskins

Featuring Deborah Nansteel, Eliam Ramos, Nina Evelyn Anderson, Joel Clemens, Carina DiGianfilippo, Isabel Randall, Chris Remkus, Naila Delgado

September 20th – 22nd

The Strand Theatre

543 Columbia Rd

Boston, MA 02125

Information here

Content Warning: Is This America? contains very strong, racially-loaded language, and references to violence.

Critique by Maegan Bergeron-Clearwood

BOSTON — Early in Act Two of White Snake Project’s new opera, Fannie Lou Hamer stands proudly before the Democratic National Convention, demanding a seat at the table for Black citizens. She testifies to the violence and dehumanization she has faced as a Black woman in the mid-twentieth century deep south: “I question America, the home of the free and the brave… They make our lives Hell! Hell, Hell! Is this America?”

Hamer’s famous speech (adapted by co-librettists Cerise Lim Jacobs and Mary D. Watkins and sung with grandeur and ferocity by mezzo-soprano Deborah Nansteel) was not met with polite applause during the performance I attended last night. Instead, a spectator a few seats to my right was moved to spontaneously respond – “Get it, girl!” – followed by cheers and uproarious applause.

This moment, which felt more like a political rally than a traditional opera performance, spoke to two factors working in the production’s favor. First is White Snake Project’s explicit efforts to eliminate gatekeeping in opera spaces: Founding Artistic Director and co-librettist Jacobs’ pre-show speech invited the audience to respond however we were moved to, and a program insert explaining various opera terms made it clear that this form of storytelling is for anyone and everyone.

This production is also indebted to the raw power of Hamer’s original words. Despite her sixth-grade education and a barrage of traumatic life experiences, Hamer became one of the loudest voices of the voting rights movement – a voice so powerful that it seems only fitting to set it to an operatic score.

The most moving aspects of Is This America? rely on Hamer’s words to do what they were meant to do: inspire. Her speeches were profound, even poetic in their straightforwardness, and the production crackles when Nansteel is singing about freedom with embodied, full-throated passion.

The text falters in the narrative’s more mundane moments. Intimate interactions feel flat compared to Hamer’s presentational speeches, resulting in a ploddingly expositional first act. There are some dramaturgically confusing structural choices as well: the narrative spontaneously switches to a past tense narrative device multiple scenes in, and some of the story’s most dramatic scenes happen offstage only to be reported on after the fact (although the choice to show instead of tell Hamer’s horrific experience of police brutality is a wise one).

The composition (by Watkins) also favors the crowd-facing scenes, with rousing, rhythmically charged cries for justice as act openers and closers. There is a sad, even dour slowness, however, to the rest of the music which drags down a story that is otherwise charged with political and emotional urgency.

Ensemble/Freedom Party. Photo by Kathy Wittman

Director Pascale Florestal fails to combat these pacing and tonal issues. During musical transitions, performers frequently appear as though they are waiting for the next scene instead of intentionally occupying space. The ensemble members are commendable vocalists, but they struggle with movement. Dynamic scenes, like political rallies and church gatherings, appear oddly static.

A few performers deserve credit for being the exceptions to this rule. Eliam Ramos, who plays Hamer’s husband, among other roles, fills the sweeping Strand Theatre with not only his rich bass-baritone vocals, but also a resonant stage presence. Ensemble member Isabel Randall, despite having only a few solos, stands out for her impassioned, expressive physicality. And, the aforementioned Nansteel embodies Hamer with a performance that is at once powerful and tender, forceful and warm.

Stage design (Baron Pugh) is minimal, relying on black and white projections (John Oluwole ADEkoje) to inform us of where and when the narrative is going. This historical, literal imagery provides the audience with basic narrative details, but little in the realm of aesthetic or emotional flavor. Meanwhile, the lack of physical dimensions (there is nothing onstage besides the projection screens and the occasional table and chair) gives the performers little to play with.

More than anything, what this production needs is more. More movement, more lyricism, more momentum, more dynamic design elements, and especially more bodies. The seven-person ensemble simply doesn’t do this sweeping story justice: the trajectory of Hamer’s political momentum is not made clear because the crowd scenes fail to grow in either size or enthusiasm. She and her fellow activists’ triumphs are powerful, but fleetingly so, never quite feeling like a collective movement.

Still, as evidenced by the enthusiastic audience that I was a part of last night, the impact of this story is clear. Hamer’s words, her belief in the power of democratic action could not come at a more pivotal time. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to hear them in such a fitting way: impassioned, proud, and loud enough to fill a 1,300-seat theater.