Wesley T. Jones as Keith Watson and Elena Hurst as Hector Tobar in “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992.” Photo: Lauren Miller

Presented by American Repertory Theater in association with Signature Theatre

Conceived, Written, and Revised by Anna Deavere Smith

Directed by Taibi Magar

Scenic Design by Riccardo Hernandez

Costume Design by Linda Cho

Lighting Design by Alan C. Edwards

Sound Design by Darron L. West

Projection Design by David Bengali

Movement Coach Michael Leon Thomas

Dialect Design by Amy Stoller

Sensitivity Specialist Ann James

Featuring Elena Hurst (she/her), Wesley T. Jones (he/him), Francis Jue (he/him), Carl Palmer (he/him), and Tiffany Rachelle Stewart (she/her).

Digital playbill

Digital guide & dramaturgy

Runtime: Two and one half hours, including one 15-minute intermission.

Aug. 28 – Sept. 24, 2022

ASL Interpreted: 9/18 at 2PM & 9/21 at 7:30PM

Audio Described: 9/17 at 2PM & 9/22 at 7:30PM

Open Captioned: 9/17 at 2PM & 9/22 at 7:30PM

Relaxed: 9/24 at 2PM

Loeb Drama Center

64 Brattle Street

Cambridge MA 02138

This production contains footage of extreme violence, instances of racialized and discriminatory language, and the sound of a gunshot.

Review by Kitty Drexel

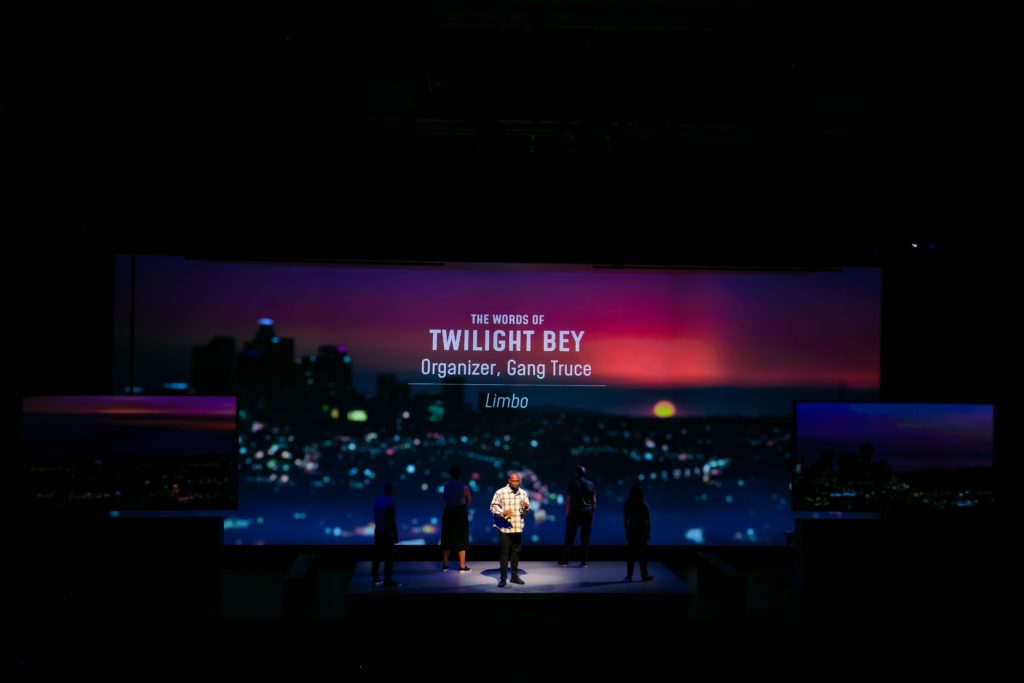

I can’t forever dwell in darkness.

I can’t forever dwell in the idea,

just identifying with people like me,

and understanding me and mine.

- Twilight Bey

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 isn’t a conversation starter. It is the continuation of a centuries-long conversation. While my fellow white people are arguing about woke politics and sniffling about their fragile feelings, BIPOC and their allies live the negative effects of systemic racism.

This play is about the violence perpetrated against Latasha Harlins, Soon Ja Du, Rodney King, and George Floyd. Graphic violence is depicted. Audience members see the moment when Latasha Harlins dies. We see LAPD police brutally and mercilessly beat Rodney King. Reginald Denny nearly died during the Los Angeles riots. This play is not for children.

The projection design by David Bengali retains its high-caliber journalism. The violence is graphic but necessary to the play’s discussion (and ours). Playwright Deavere Smith and director Taibi Magar include the footage to ensure that the audience fully understands the context of the play. I imagine that Deavere Smith and Magar decided to include the footage for reasons similar to Mamie Till requesting an open casket: people should know what was done. Racism has a human cost. We must witness the violence to prevent more violence.

The playwright and director weighed the audience’s right to know with the sensitivities of a New England audience. They took the risk that we could handle it. Please consider your own needs when purchasing tickets. Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 is excellent, but no production is worth the cost of one’s mental health.

A.R.T.’s production differs greatly from Deavere Smith’s original work. Instead of a solo actor, it has five. This production is much longer and includes new interviews. The 2022 production at A.R.T. expands its discussion to include the COVID-19 quarantine and the murder of George Floyd.

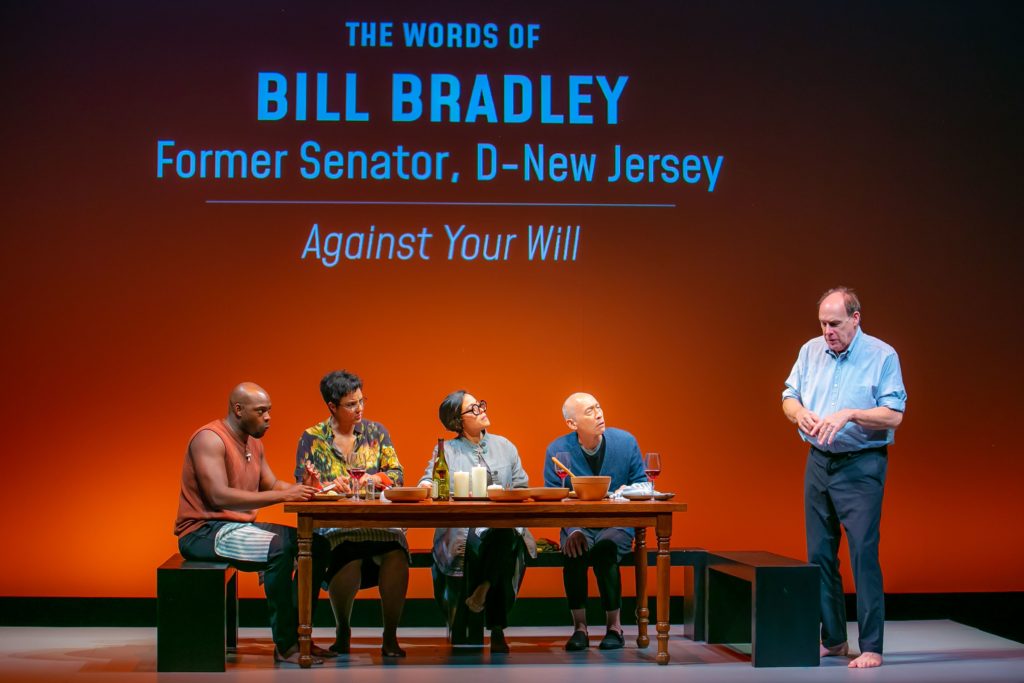

Wesley T. Jones as Paul Parker, Tiffany Rachelle Stewart as Elaine Brown, Elena Hurst as Alice Waters, Francis Jue as Rev. Tom Choi, and Carl Palmer as Bill Bradley in Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992. Photo: Lauren Miller

One of the new sections is a dinner scene, “A Dinner Party That Never Happened,” in which folks from all manner of lifestyles sit at a table and discuss race over dinner. It represents the conversations we should all be having. Everyone has a seat at the table where anti-racist ideas are shared.

Despite the great efforts of the cast and creative crew, the dinner party is incongruent with other scenes. It is because the wonderfully talented actors remain seated throughout. Their sitting draws their energy down. Their energy sinks into the stage below them instead of reaching out to the back of the theater like in previous scenes.

The fourth wall, previously lifted, was lowered for the dinner party to create a new reality in which the audience is unseen and unheard. It wasn’t immediately clear whether the audience’s resulting discomfort was intentional or not. The sudden arrival of the fourth wall might symbolize the discomfort people experience when they are left out of a conversation. Or, it could be the unintentional consequence of seating all five actors at a table in a large theater during a three-hour play. One is a risky choice worth taking. The other is unfortunate.

Cast members Elena Hurst, Wesley T. Jones, Francis Jue, Carl Palmer, and Tiffany Rachelle Stewart perform brilliantly in a broad range of roles that challenge and reveal their many talents. They are shop owners, journalists, kids, adults, scholars, politicians, jurors, activists, rioters, and a cop.

Wesley T. Jones as Twilight Bey in “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992.” Photo: Lauren Miller

Fellow actors take note: theirs is quick but intricate work. Sometimes the cast switched characters in mere seconds by donning a new costume piece. Sometimes they shifted posture and spoke directly into a new character. Wesley T. Jones plays past NRA president Charlton Heston with appropriate arrogance by donning a red robe. Francis Jue transformed into dramatic soprano Jessye Norman before our eyes as he crossed the stage in a headdress and gown.

There are a few instances when actors play a race other than their own. This was done because a second, silent actor was needed for a scene and to give an actor time to transition into another scene. It was not colorblind casting.

Race bending in Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 does not give other theatre companies permission to do it too. We are given the impression that the cast, director, and writer made conscious choices. Actors are not trying on a different race for the sake of convenience.

I am of the opinion that these choices worked for this production, but I am well aware that my opinions aren’t necessarily shared by the entire theatre community. Professional theatre companies with a majority-white leadership should never attempt race bending, colorism, or, god forbid, blackface without the input of consenting, well-compensated community representatives.

Community and fringe theatres should take a nap and pretend they never considered race bending for their show. (You don’t have the resources. You will fuck it up. Instead, focus on why you can’t retain any BIPOC actors. But, I digress.)

Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 is… a lot. Firstly, it is good theatre and great art. It may trigger white guilt and white fragility. To that I say, while we did not personally enslave anyone, we still have a responsibility to dismantle the racist systems enacted by our distant and not-so-distant ancestors.

Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 sums up the conversation until now. Previous conversations did not include the hate experienced by the AAPI community. This production rightfully extends the conversation to them. None of us are free until we are all free together.

New England Theatre Geek published Afrikah Smith’s review of Newton Theatre Company’s production of Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 in 2021. It is HERE.