Preface: This article was originally submitted to HowlRound for potential publication in 2017. The truly wonderful folks there decided to go in a different direction. The article is published on NETG to continue the conversation started last August by EJ. Other disabled artists interested in sharing their stories should please contact the Queen to discuss.

-Kitty, the Queen Geek

End Preface

In her excellent article summarizing the breakout session at the 2017 Theatre Communications Group Annual Conference in Portland, OR called “Creative Access: Accommodations for Professional Performers with Disabilities,” Talleri McRae lists five salient points to guide theatre professionals towards more ability inclusive practices. Her suggestions were on point. They hit me where I live. In this article, I reflect on my experiences as a disabled artist. Were the practices suggested by McRae’s article applied across the theatre world, my experiences as a child and young-adult artist would have differed greatly. If universally implemented today, the impact will affect disabled performers for generations to come.

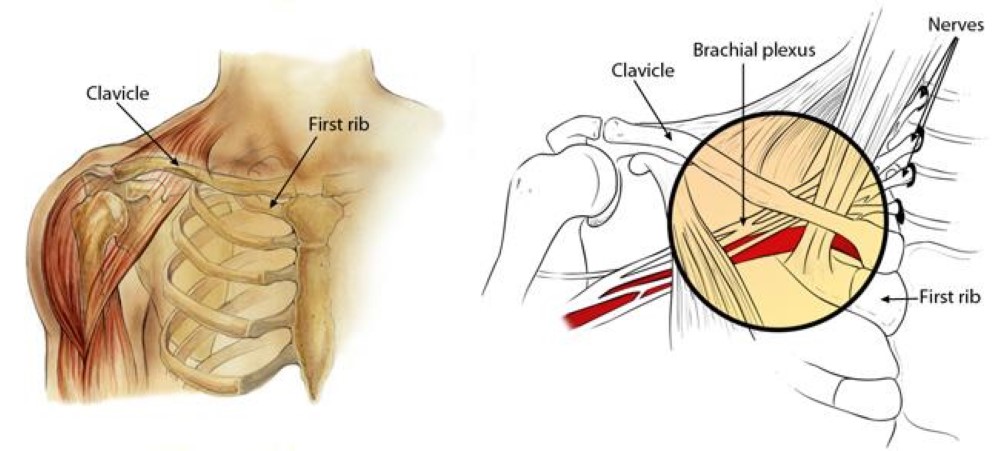

I am an artist living with Erb’s Palsy (aka the sexiest of the palsies). More information on Erb’s, a form of Brachial Plexus Palsy, can be found HERE. In layman’s terms: I was intercepted by maternal complications during my escape from the womb. The good doctor was kind enough to rip me out by the stem.

The shoulder and brachial nerves. source: http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00077

My disability is mostly invisible. The majority of society, including close friends, audition panels, and potential employers remain blissfully unaware of my limitations. Fellow humans don’t see my disability because their expectation is that I am fully abled. People see what they expect to see. I have come to understand that a person’s perception of me isn’t my responsibility. Everyone has their something that they’re working through.

The reactions of strangers have both negative and positive influences on my theatre career. For example, I have purposely hidden my disability at dance calls lest someone misjudge how my disability might affect my role as a non-dancing ensemble member. Other negative complications have included being treated as an invalid, as well as tokenism.

As an active, relatively known artist in the Boston area, I can trust that my reputation/work precedes me at some auditions. My disability is disclosed on my resume, in my email and on my websites. In the past, the potential risk outweighed the potential gains. I have previously refused to work with a company that couldn’t see my talent for my differences. Young or new artists cannot be so assured. “Coming out” as disabled can be disastrous.

Years ago, I was auditioning for a role in a park-and-bark opera for a now defunct company when my ability to perform came into question. A producer asked the panel (even though I was standing right there) if my “arm thing” would prevent me from adequately singing the role. She cruelly questioned my intelligence because my body was (to her) unreliable. I should have told the panel that they might truss me up like David Bowie on SNL, and I’d still sing the hell out of it. Instead, I patiently informed her that I was a flexible artist willing to adjust for the performance’s needs. I was cast but the producer required periodic assurances that I met her standards.

Exceptional rudeness aside, the producer grossly misunderstood my disability. She should have asked me directly if accommodations would be needed. A question on the audition form would have sufficed. The lesson I learned was to avoid this producer, and to passionately warn my fellow artists against working with this company. If proper behavior towards members of the disabled community is in question, it is best to err on the side of compassion and extreme courtesy. The internet may be dark and full of terrors but it is also full of suggestions. Phamaly Theatre Company, a theatre represented at the “Creative Access: Accommodations for Professional Performers with Disabilities” panel has some excellent recommendations.

Conversely, there are colleagues who’ve discovered my disability after casting who have kindly shared their secret physical limitations as well. We worried that if we were up front with our disabilities that we wouldn’t be cast in the first place. Our transparently shared stories made our production safer places for ability diversity, but we had to be cast first. Overcoming that fear takes trust.

It is important to note that not all disabled actors require physical accommodations. I’m lucky that I personally don’t require many accommodations within an audition, rehearsal or performance setting. Because I’m so capable, I sometimes feel like I’m not disabled enough. To make matters worse, professional acquaintances have told me that i don’t “look disabled.” They’ve told me in the next breath that they haven’t noticed, or that they don’t think of me that way. Several have suggested that my disability is in my mind. Another has told me that God will heal me if I “pray hard enough.” It is incredibly difficult to work with such disrespectful micro-aggressions. If a colleague is willing to say such things when it didn’t matter, what drivel would they spout when it did?

I was a stagehand in the workstudy student at my alma mater in 2002. My job that night was to hand out programmes to patrons entering the theater. At the time, the main stage was up a short staircase. A patron in a wheelchair, ticket in hand asked me where the elevator to the seats was. The house manager next to me replied that there wasn’t one. Several of the patron’s friends were called upon to lift him, carry him up the stairs and seat him in the aisle. The theatre didn’t even have assigned accessibility seats.

At seeing the cumbersome effort exerted by patrons, a prominent Conservatory Leader (CL) who saw the scene play out, loudly insisted that the disabled patron was willing to go to great lengths for great music. CL completely ignored the patron’s humiliation. I was deeply embarrassed that CL would belittle the man’s plight. Further, if a theatre cannot accommodate the physically disabled, this information should be made as obvious as possible to everyone. Accessibility should not include any guess work. Disabled patrons deserve the same respect and privacy as fully abled patrons.

The disabled are experts on the own disabilities. We are not experts on every disability. We cannot be called upon to be an expert on another’s body. That being stated, a commitment to ability inclusivity requires that a theatre remain steadfast in their mission to be inclusive in practice as well as philosophy. To start, question stigmas, and stereotypes within the company. Active introspection on theatre practices will aid actors as well as enhance your group’s capacity for compassion. Next, work to protect the vulnerable from micro and macro-aggressions. If you encounter ablism, gently correct the offender. Create a policy within your organization to educate your employees. Lastly, representation matters. Dramaturgy can be useful in understanding the limitations of the disabled. Welcome members of the disabled community as consultants into the creative process. Keep asking them to return to subsequent projects. A casting and consultation note put placed in the program for transparency’s sake. A consult isn’t as good as hiring a disabled actor, but it communicates to an audience that the experiences of the disabled community are considered important to the theatre. The Screen Actors Guild has a handy booklet to answer related questions.

As a critic and an independent artist, it’s important to me to recognize whether a theatre’s failure to include the disability community is an unintentional error, or a blatant act of ignorance. Theatre’s that practice radical inclusivity and open-minded identity politics attract loyal actors, volunteers, and audience members of all abilities. Human beings are imperfect by design. Just as an artist refuses to give up on their craft after a failed audition, it is tantamount to a theatre’s accessibility mission to admit to failure and to strive towards a remedy. We the disabled want to be represented in and by the theatre. The best way a theatre can help the disabled community is by giving us a voice in the conversation. When all are welcome; all will enjoy.

This blog post references the article, “Creative Access: Accommodations for Professional Performers with Disabilities” by Talleri McRae, posted on HowlRound on August 11, 2017. McRae’s article is used with her permission. Concerned parties should contact Mrs. Drexel privately with comments or feedback regarding usage. McRae’s article, also referenced at top, can be found HERE.